Cannabis Use in Canada

Current Policies, Prevalence Trends, Socioeconomic and Demographic Correlates

- Daniel J Corsi, PhD

Contents

Study Team

Daniel J Corsi, PhD

Dr. Corsi received his PhD in Population and Public Health in 2012 from McMaster University. He completed his postdoctoral training at the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies in 2014, where he specialized in innovative methods to understand the influence of socioeconomic status on health and a focus on substance use epidemiology. He is a Scientist with the CHEO Research Institute and an Assistant Professor at the University of Ottawa.

Gabrielle Pratt Tremblay

Gabrielle Pratt Tremblay is a HBSc student in Environment with a concentration in ecological determinants of health at McGill University. Her research interests include the areas of environmental determinants of health, perinatal epidemiology, and women’s health. She will start her master’s in epidemiology in the fall of 2024.

Acknowledgments

A grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research partially funded this work. We want to thank the OMNI Research Group and BORN Ontario for their support in preparing some of the research related to cannabis in pregnancy. Dana Lowry was a former student of Dr. Corsi, who was involved in the cannabis trends analyses.

Highlights

Background: The Canadian Government legalized cannabis use in October 2018 through the Cannabis Act, targeting individuals aged 18 and older. The act aims to prevent youth access, ensure adult public health and safety, and curb illegal distribution profits. While federal regulations were established, provinces and territories played a vital role in refining and implementing specific restrictions. This report provides a comprehensive overview of cannabis-related policies, including usage trends, demographics, socioeconomic factors, stigma, and health impacts in Canada.

Research Methods: The research encompasses a variety of studies, with a focus on cannabis use, use during pregnancy and associated health impacts. National surveys, such as the Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (CTUMS), Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Monitoring Survey (CADUMS), and Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS), were analyzed to understand usage patterns over time and among different demographic groups. Long-term and recent cannabis use behaviours were explored, considering factors like age, sex, education, tobacco smoking, province of residence, and recent pregnancy. We also summarize relevant research obtained from online database searches and reference lists.

Policy Information: Cannabis policies and regulations were obtained directly from federal and provincial websites. The legal age for purchasing cannabis varies from 18 to 21 years old depending on the province. Restrictions on household cannabis amounts and regulations regarding cannabis growth also vary by province. Smoking regulations, especially in conjunction with tobacco, vary by region. However, driving under the influence of cannabis is prohibited uniformly across all provinces. The possession limit of dried cannabis is uniformly restricted to 30g in all provinces and territories. Legislative changes are ongoing, with jurisdictions adapting to new public health concerns and federal updates.

Qualitative Insights: To explore stigma and cannabis use during pregnancy, qualitative interviews were conducted with obstetric patients in Ontario who had used cannabis during their pregnancy. Participants were eligible if they were at least 16 years old, pregnant, or recently postpartum, and had used cannabis during their current or recent pregnancy.

Recent Usage Trends: Data from 2019-2022 reveals no significant changes in past 30-day cannabis use. The age-adjusted prevalence was approximately 11-12% in men and 7% in women. A moderate increase in past 30-day cannabis consumption was noted in women, from 6.5% to 7.8%. Men exhibit a higher likelihood of cannabis use than women, with 14% of men and 8% of women reporting past-year use (2002-2019). Prevalence varies by age, peaking at 34.3% for men and 23.5% for women in the 20-24 age group. Notably, tobacco smoking strongly correlates with cannabis use, with current smokers over six times more likely to use cannabis in the past year (odds ratio: 6.4) and over eight times more likely in the past 30 days (odds ratio: 8.3) compared to never-smokers.

Socioeconomic Factors: Cannabis use exhibits complex relationships with socioeconomic status (SES). An inverse association with education level is observed, particularly in men, with those with less than a high school education being more likely to use cannabis. However, the relationship becomes nuanced when accounting for tobacco smoking, revealing a positive association between education and cannabis use. This suggests that the socioeconomic differentials for cannabis use may be influenced by tobacco use. Further exploration is needed to understand the impact of cannabis legalization on SES patterning.

Geographic Variation: The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of past-year cannabis use is 7.6%, varying across provinces, with Saskatchewan at 6.5% and Nova Scotia at 10.3%. Quebec has the lowest past-30-day prevalence (6.7%), while Nova Scotia has the highest (14.7%). Geographic differences may result from policy variations, price disparities, and accessibility issues post-legalization. Social acceptability, socioeconomic, demographic, and health service access differences may also contribute to regional cannabis use patterns.

Cannabis Use in Pregnancy: Analysis of survey data (2002-2019) on recently pregnant individuals (n=3,243) showed a 10% cannabis use rate, with 4.6% reporting use during their last pregnancy. Younger women (15-24 years) and those with lower education levels exhibited higher odds of cannabis use. Qualitative interviews and retrospective studies identified stigma, disclosure hesitancy, and potential health risks as important themes related to cannabis in pregnancy.

Stigma and Medical Cannabis Use: Stigma around medical cannabis poses a barrier for individuals with chronic illnesses seeking alternative treatments. Healthcare professionals’ attitudes influence recommendations, contributing to societal stereotypes. Initiatives like public education campaigns are proposed to address and reduce this stigma.

Potential Health Effects: We summarize the physical, neurological, and psychosocial consequences of using cannabis. These include cardiovascular effects, neurological impairments, anxiogenic reactions, metabolic and respiratory conditions, and impacts on female reproductive health. Consistent and long-term use is linked to numerous adverse outcomes, highlighting the need to be aware of and address potential health risks.

Cannabis Use and Youth Mental Health: Regular cannabis use in youth can structurally damage the brain, impacting mental health. Robust evidence links youth cannabis use to increased rates of depression, suicidal behaviours, anxiety, and poor mental health outcomes. Despite this, Canadian youth exhibit high rates of cannabis consumption, indicating a need for awareness and intervention.

Conclusion: This report provides a detailed overview of cannabis trends, policies, and health impacts in Canada. Analyzing usage patterns, socioeconomic factors, and regional variations is vital for making informed decisions regarding policymaking and public health initiatives. Further research is necessary to gain a better understanding of the intricate relationships between cannabis use, socioeconomic status, and regional dynamics. In addition, certain groups, such as Canadian youth and pregnant individuals, are at high risk for cannabis consumption, which can have potential health risks. Therefore, tailored interventions and educational programs are necessary to reduce consumption in these groups.

Introduction

Background

In October 2018, the Government of Canada introduced the Cannabis Act, which legalized recreational cannabis use nationally.1 Even before legalization, cannabis was widely used, with one in five adults (22%) reporting past-year use in 2018, according to the Canadian Cannabis Survey.2 This figure increased to 26% in 2023, the most recent estimate of cannabis use from this survey.

Research Methods

Our cannabis research has been widely published, particularly in the area of cannabis use in pregnancy and the potential health impacts on the mother and infant.8–16 Here, we’ve summarized some of our publications and other recent studies on Cannabis use in Canada. To better understand the patterns of cannabis usage across Canada, we have conducted extensive analyses of national surveys that focus on substance use. These surveys include the Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (CTUMS), conducted annually between 2004 and 2012; the Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Monitoring Survey (CADUMS), conducted annually between 2008 and 2012; and the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS) which was conducted biennially in 2013, 2015, and 2017. In addition, we also have data from the Canadian Alcohol and Drug Survey (CADS) conducted in 2019 and the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) conducted annually between 2019 and 2022, which replaces the CTUMS. These surveys provide valuable insights into the usage trends of cannabis over time and among different demographic groups.

Our main focus was to understand long-term cannabis use measured by whether individuals had used cannabis in the 12 months before the survey. To capture more recent cannabis use behaviour, we also look at use within the past 3 months and past 30 days.

We included several demographic and socioeconomic factors, including respondent age, sex, level of education, tobacco smoking, province of residence, and recent pregnancy.

We combined the survey data to analyze trends, considering the sampling weights to ensure the results represented the entire population. We use the weighted prevalence (the estimated percentage adjusted for non-responders and excluded populations) of past-year cannabis use for each survey year, looking at different sociodemographic characteristics and provinces. We also used statistical methods, like logistic regression, to adjust the estimates for age, education, and tobacco smoking.

Information on Cannabis policies and regulations was obtained directly from federal and provincial websites, and we provide links to these sites below. To examine the stigma around cannabis use and cannabis use in pregnancy, we conducted qualitative interviews with obstetric patients in Ontario who used cannabis in pregnancy. Patient participants were eligible if they were at least 16 years of age, were pregnant or recently pregnant (up to 6 months postpartum) at the time of the interview and had used any form of cannabis during their current or recent pregnancy. Finally, other relevant research is collected through online searching of electronic databases and reference lists of published research. We include an extensive reference list and bibliography.

Overview of Cannabis-Related Policy in Canada

In October 2018, the Canadian Government officially legalized cannabis use for those 18 years of age and older. The legal framework that was established to control the production, distribution, sale and possession of cannabis across Canada is known as the Cannabis Act.

The primary aims of this act are to 1) keep cannabis out of the hands of youth, 2) protect public health and safety by allowing safe access to adults, and 3) keep the profits out of the pockets of illegal distributors (Cannabis Act, 2018).

While the federal government established the foundational regulations, it is important to note that provincial and territorial jurisdictions also play a crucial role in refining and implementing specific restrictions. Here, we summarize the pertinent restrictions imposed by the Cannabis Act and specific modifications implemented by each province. These tables aim to illustrate the pertinent restrictions imposed by federal, provincial, and territorial governments concerning cannabis use.

While much of the provincial and territorial cannabis legislation is similar to the federal legislation, variances exist. For example, provinces vary in their legal age for purchase, ranging from 18-21 years of age. British Columbia, Quebec and Nunavut are the only governments that have put a restriction on the amount of cannabis permitted per household. Manitoba and Quebec have both banned the growth of cannabis in residences, while the rest of Canada allows the growth of up to four cannabis plants per household. Most governments prohibit the smoking of cannabis in the same areas as tobacco; however, specifics vary by province and territory. Across all provinces and territories, the consumption of cannabis in or before the operation of a vehicle remains illegal. Finally, all provinces and territorial governments have uniformly limited personal possession of cannabis in public places to 30g of dried cannabis or its equivalent. Cannabis legislation and regulations continue to evolve in Canada. Provinces and territories may amend their laws in response to emerging public health concerns or federal updates.

Table 1.

Federal Cannabis Regulations in Canada

Federal

Legislation and date

The Cannabis Act (June 2018; amend. April 2023)

Legal age for purchase

- 18 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- It is prohibited to sell cannabis or a cannabis accessory that has an appearance, shape or other sensory attribute or a function that there are reasonable grounds to believe it could be appealing to young persons.

Marketing

- Prohibited for an authorized seller to display it, in a manner that may result in the cannabis, package or label being seen by a young person.

- Prohibited to promote cannabis (including cannabis accessories and services):

- By means of testimonial or endorsement,

- In a way that could be seen by youth,

- By means of the depiction of a person, character or animal, whether real or fictional or

- By presenting it or any of its brand elements in a manner that associates it with or evokes a positive or negative emotion about or image of, a way of life such as one that includes glamour, recreation, excitement, vitality, risk or daring.

Use / Where people can vape

- The Smoke-Free Environment Act 2005 prohibits the use of electronic cigarettes in indoor public places, healthcare facilities, childcare facilities, workplaces, post-secondary institutions, restaurants, licensed liquor establishments and in motor vehicles while persons under the age of 16 are present.

Notes

Provincial Cannabis Regulations

The major components of Cannabis regulations are summarized below for each province:

British Columbia

Legislation and date

Cannabis Distribution Act (July 2018, amend. June 2021)

Cannabis Control and Licensing Act (October 2018, amend. January 2023)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- A licensee may not sell cannabis or cannabis accessories through self-service displays or by means of a dispensing device.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time (does not apply to medical cannabis).

- A household cannot possess more than 1, 000g of dried cannabis (or equivalent).

Notes

- It is prohibited to smoke/vape cannabis in (or on):

- Indoor common areas in condos, apartment buildings and university/college residences, public places and enclosed workplaces, a health board property, a skating rink, sports field, swimming pool, playground or skate part, a deck, seating area or viewing area, a park, a regional park, or any stops for trains, buses, taxies or ferries.

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- A vehicle or boat that will be or is being driven

- A school or on school property

Alberta

Legislation and date

Bill 26: An Act to Control and Regulate Cannabis (December 2017) [amended the Gaming and Liquor Act]

Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Act (June 2018, amend. December 2022)

Legal age for purchase

- 18 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit, whether in person, online or over the phone.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- No limit on amount of cannabis permitted per household.

Notes

- It is prohibited to smoke/vape cannabis in or within a prescribed distance from any of the following:

- A hospital property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), on a child care facility property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a school property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a workplace, in a public place, a playground, a sports or playing field, a skateboard or bicycle park, a zoo, an outdoor theatre, a public outdoor pool or splash pad, etc.

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- Any motor vehicle (public or private) that will be or is being driven

- Exception: parked RV if used as a temporary residence

- Any motor vehicle (public or private) that will be or is being driven

Saskatchewan

Legislation and date

The Cannabis Control Act (October 2018, amend. May 2023)

The Cannabis Control Regulations (October 2018)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- A license holder may not sell cannabis or cannabis accessories through self-service displays or by means of a dispensing device.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- No limit on amount of cannabis permitted per household.

Notes

- It is prohibited to smoke/vape cannabis in or within a prescribed distance from any of the following:

- A childcare facility property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a school property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a workplace, a public place (including but not limited to: parks, playgrounds, cinemas, outdoor theatres or other places of public resort or amusement), a campground, etc.

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- Any motor vehicle (public or private) that will be or is being driven

Manitoba

Legislation and date

The Liquor, Gaming and Cannabis Control Act (October 2018, amend. May 2023)

The Smoking and Vapor Products Control (May 2021)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit, whether in person, online or over the phone.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- No limit on amount of cannabis permitted per household.

Notes

- It is prohibited to smoke/vape cannabis in or within a prescribed distance from any of the following:

- A childcare facility property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a school property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a workplace, a public place (including but not limited to: parks, pools, sports venues, outdoor entertainment venues, an outdoor patio or deck that is not residential), a group living facility, etc.

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- Any motor vehicle (public or private) that will be or is being driven.

- Growing non-medical cannabis at home is prohibited in the Province of Manitoba.

Ontario

Legislation and date

Cannabis Control Act (December 2017, amend. March 2022)

Cannabis License Act (October 2018, amend. June 2023)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit, whether in person, online or over the phone.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- No limit on amount of cannabis permitted per household.

Notes

- It is prohibited to smoke/vape cannabis in or within a prescribed distance from any of the following:

- A childcare facility property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a school property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a workplace, common areas in condos, apartment building and collegiate residences, healthcare service buildings (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a public place (including but not limited to: parks, playgrounds, cinemas, outdoor theatres or other places of public resort or amusement), in restaurants and on bar patios, etc.

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- A vehicle (public nor private) or boat that will be or is being driven

Quebec

Legislation and date

Cannabis Regulation Act (October 2018, amend. May 2022)

Legal age for purchase

- 21 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

- The sale of topical cannabis products or vape juices containing cannabis is not permitted.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- A household cannot possess more than 150g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) collectively.

Notes

- It is prohibited to smoke/vape cannabis in or within a prescribed distance from any of the following:

- A childcare facility property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a school property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a healthcare facility, a workplace, a correctional facility, a public place (including but not limited to: parks, pools, sports venues, outdoor entertainment venues), etc.

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- A vehicle (public nor private) or boat that will be or is being driven

- Growing non-medical cannabis at home is prohibited in the Province of Quebec.

New Brunswick

Legislation and date

Cannabis Control Act (October 2018, amend. April 2022)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

- Cannabis bought online through Cannabis NB can only be delivered within New Brunswick.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- No limit on amount of cannabis permitted per household.

Notes

- It is only permitted to consume cannabis in:

- A private dwelling or on land adjacent to a private dwelling (except if there is a private school or childhood center located in or on the premises of the dwelling).

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- Any motor vehicle (public or private) that will be or is being driven.

Nova Scotia

Legislation and date

Cannabis Control Act (October 2018, amend. November 2021)

Smoke-free Places Act (January 2003, amend. March 2020)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- No limit on amount of cannabis permitted per household.

Notes

- It is prohibited to smoke/vape cannabis in or within a prescribed distance from any of the following:

- A childcare facility property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a school property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a workplace, a health-care facility, a public place (including but not limited to: parks, pools, sports venues, outdoor entertainment venues, an outdoor patio or deck that is not residential), a group living facility, etc.

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- Any motor vehicle (public or private) that will be or is being driven.

Prince Edward Island

Legislation and date

Cannabis Control Act (October 2018, amend. December 2018)

Cannabis Control Regulations (October 2018)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- No limit on amount of cannabis permitted per household.

Notes

- It is only permitted to consume cannabis in:

- A private dwelling or on land adjacent to a private dwelling (except if there is a private school or childhood center located in or on the premises of the dwelling).

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- Any motor vehicle (public or private) or boat that will be or is being driven.

Newfoundland and Labrador

Legislation and date

Cannabis Control Act (October 2018, amend. June 2020)

Cannabis Consolidation Act (December 2018, amend. June 2021)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- No limit on amount of cannabis permitted per household.

Notes

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis in or within a prescribed distance from any of the following:

- A childcare facility property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a school property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a workplace, a health-care facility, a public place (including but not limited to: parks, pools, sports venues, outdoor entertainment venues, an outdoor patio or deck that is not residential), a group living facility, etc.

- Any motor vehicle (public or private) or boat that will soon be or is being driven.

Yukon

Legislation and date

Cannabis Control and Regulation Act (October 2018, amend. December 2021)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- No limit on amount of cannabis permitted per household.

Notes

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis in or within a prescribed distance from any of the following:

- A childcare facility property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a school property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a workplace, a health-care facility, a public place (including but not limited to: parks, sports venues, outdoor entertainment venues), a group living facility, etc.

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- Any motor vehicle (public or private) or boat that will be or is being driven.

Northwest Territories

Legislation and date

Smoking Control and Reduction Act (August 2019)

Cannabis Products Act (October 2018, amend. October 2023)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- No limit on amount of cannabis permitted per household.

Notes

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis in or within a prescribed distance from any of the following:

- A childcare facility property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a school property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a workplace, a health-care facility, a public place (including but not limited to: playgrounds, sports venues, outdoor events), a group living facility, etc.

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- Any motor vehicle that will be or is being driven.

Nunavut

Legislation and date

Cannabis Act (June 2018)

Cannabis Regulations (June 2020)

Legal age for purchase

- 19 years of age +

Sale/purchase restriction(s)

- Retail stores are not authorized to sell an individual more than 30g of cannabis in a single visit.

- The sale of cannabis to persons who are or appear to be intoxicated is prohibited.

Possession restriction(s)

- Legal-aged consumers are not permitted to possess more than 30g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) in a public place at any time.

- A household cannot possess more than 150g of dried cannabis (or equivalent) collectively.

Notes

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis in or within a prescribed distance from any of the following:

- A childcare facility property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a school property (including the building, grounds and parking areas), a workplace, a health-care facility, a public place (including but not limited to: playgrounds, sports venues, outdoor events), a group living facility, etc.

- It is prohibited to consume cannabis (smoke, vape, and eat) in:

- Any motor vehicle that will be or is being driven.

Results

Correlates of Cannabis Use

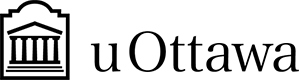

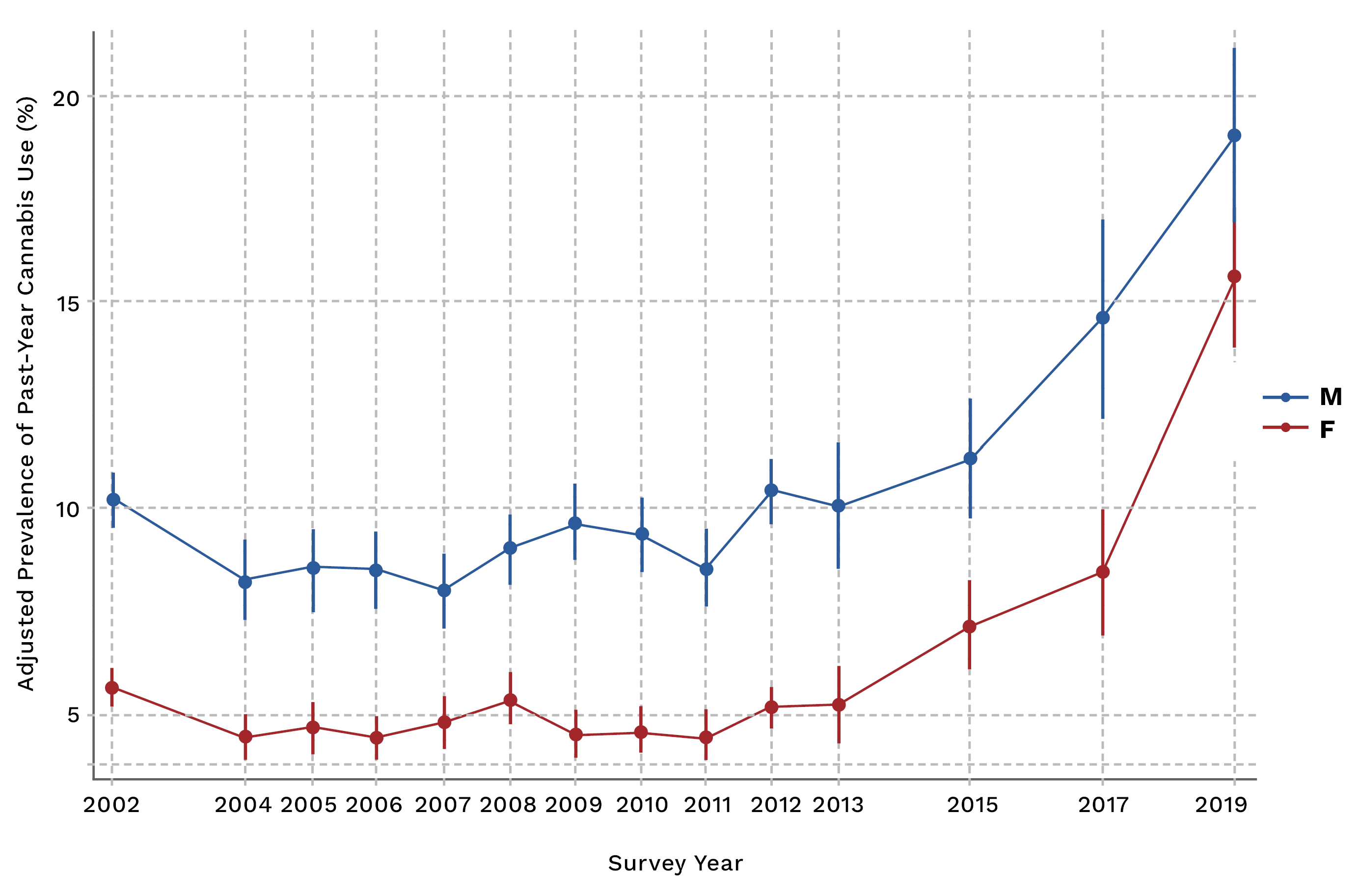

Overall, men are more likely to use cannabis than women, with 14% of men and 8% of women reporting past-year use in our dataset that covers 2002-2019. Sex differences were consistent in all study years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prevalence of Past-Year Cannabis Use in Canada, by sex, 2002-2019.

This figure shows the weighted prevalence of past-year cannabis use for males (M) and females (F), calculated from the following surveys, CADS, CADUMS, CAS, CCHS, CTADS, and CTUMS for 2002-2019.

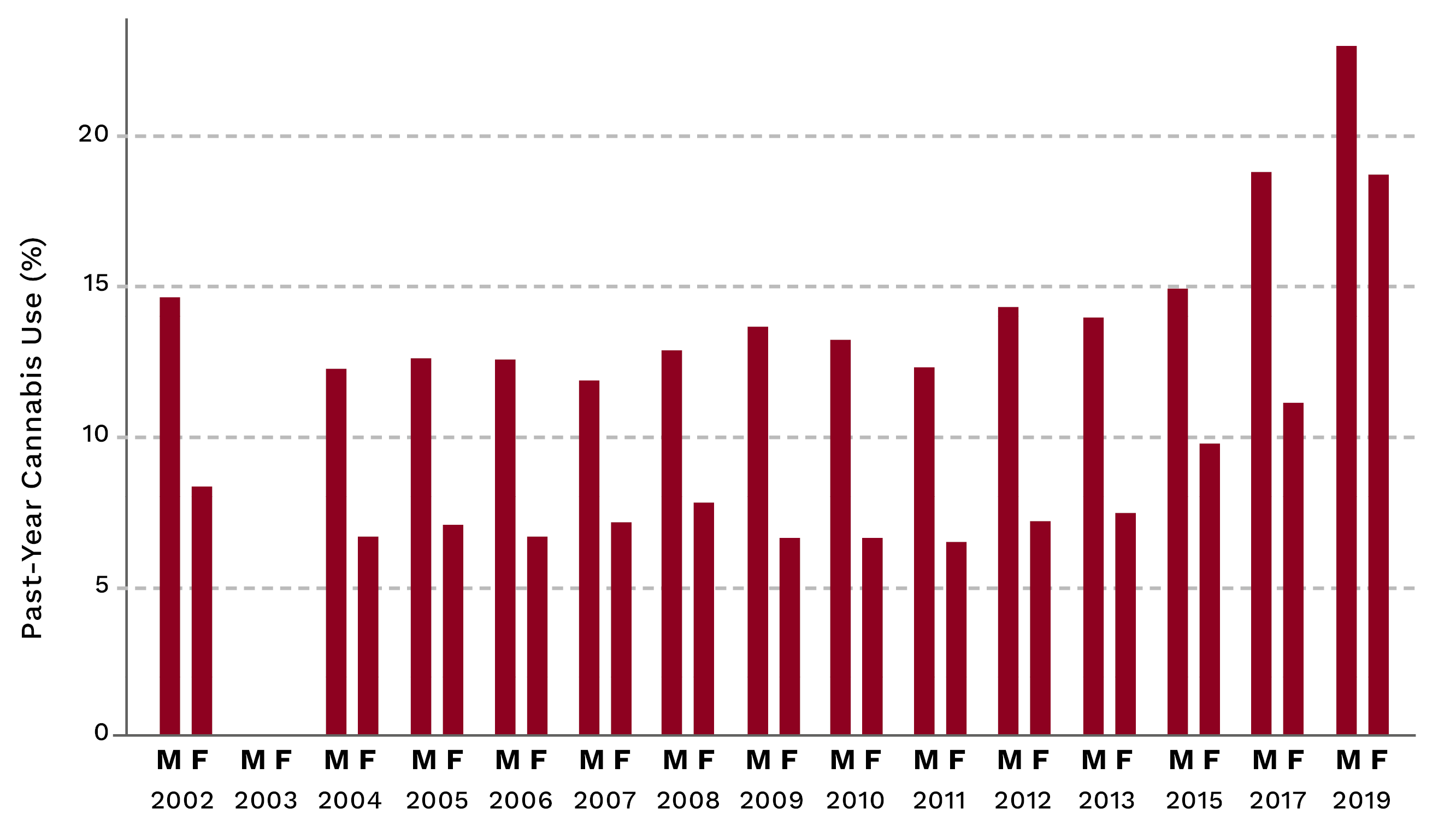

Cannabis use is linked to age, peaking at 34.3% for men and 23.5% for women in the 20-24 age group. Older individuals, 65 years and above, had lower cannabis use rates (1.8% in men and 0.9% in women) (Figure 2). The pattering was similar in the analysis of past 30-day cannabis use by age. However, using this measure of cannabis use, adults aged between 25 and 34 years had a higher prevalence of use compared to those aged 15-19y; 24% vs 12% in males and 16% vs 12% in females. The gender gap was less pronounced in this metric, especially at ages 15-19 with 12.1% of males reporting cannabis use within 30 days compared to 11.6% of females. Finally, there were higher rates of use in among seniors aged 65 and above, with 5.1% of men and 1.7% of women in this demographic using cannabis. These data were based on the CTNS, the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey and collected within the past 5 years.

Figure 2. Prevalence of Past-Year and Past-30-Day Cannabis Use, Canada, by sex, 2002-2019 for Past-Year Use and 2019-2022 for Past-30-Day Use (from CTNS 2019-2022).

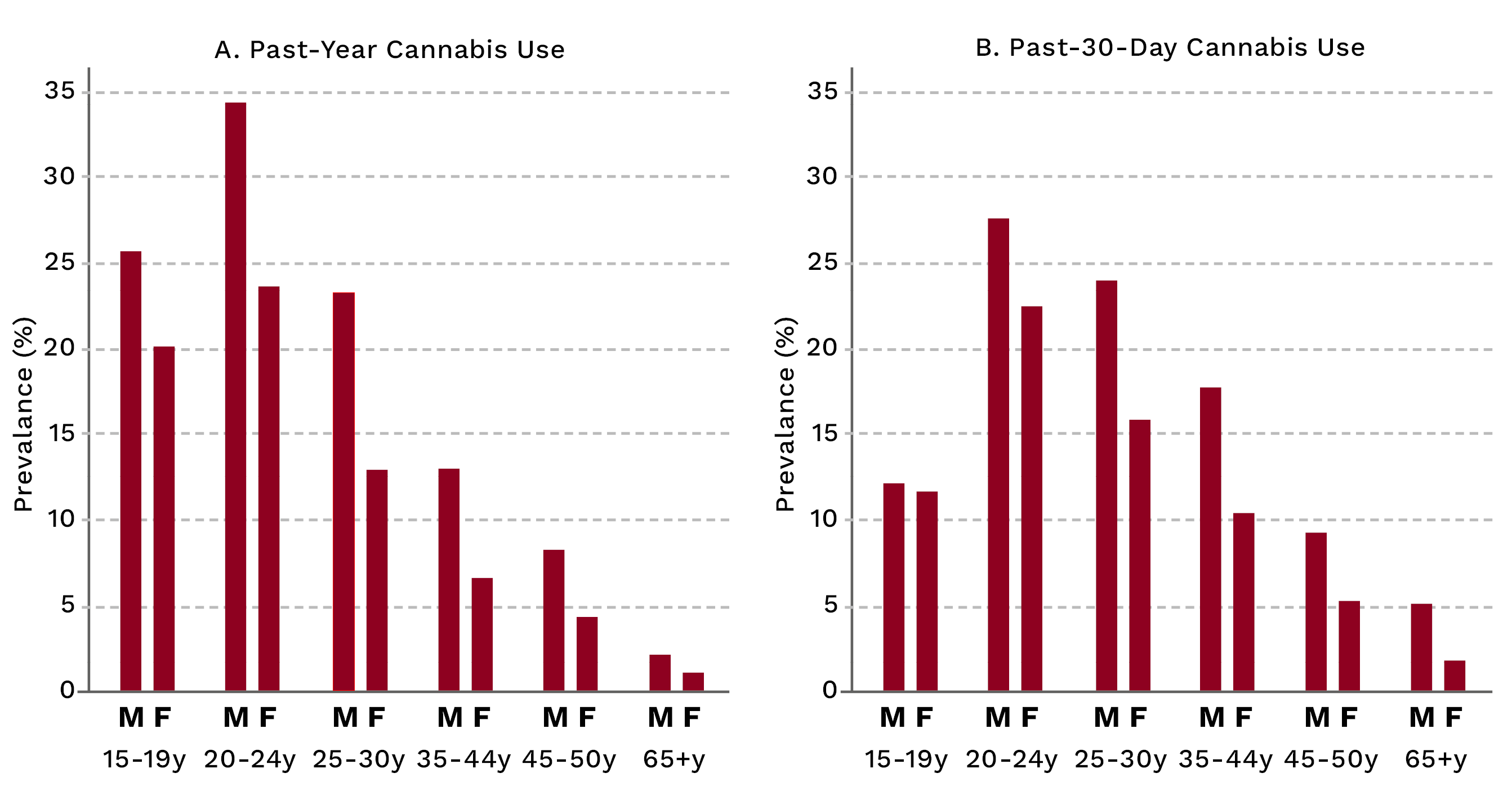

Tobacco smoking was strongly associated with cannabis use, and after accounting for age, current smokers were over six times more likely to use cannabis in the past year (odds ratio: 6.4; 95% CI: 6.0-6.8) and more than eight times more likely to use cannabis in the past 30 days (odds ratio: 8.3; 95% CI: 7.3-9.5) compared to never-smokers. Former smokers were also more likely to use cannabis compared to never-smokers, and the patterns were consistent in men and women (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Adjusted Prevalence of Past-Year and Past-30-Day Cannabis Use, Canada, by sex, by current smoking, 2002-2019 for Past-Year Use and 2019-2022 for Past-30-Day Use (from CTNS 2019-2022).

The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of past-year cannabis use was 7.6%, and this varied between 6.5% in Saskatchewan and 10.3% in Nova Scotia. British Columbia had the second-highest prevalence (10%). The prevalence of cannabis use in the past 30 days, after adjustment, was found to be 8.9%. However, this percentage varied across provinces. Quebec had the lowest prevalence at 6.7%, while Nova Scotia had the highest at 14.7%. The other Atlantic provinces, namely Newfoundland & Labrador (10.2%), Prince Edward Island (10.2%), and New Brunswick (12%), all had a higher prevalence of cannabis use in the past 30 days, exceeding 10%. British Columbia had a prevalence of 10.4%. The geographic variation in cannabis use in Canada may be due to several factors. First, some of the variation may be due to policy differences that we will examine in more detail. In addition, there are differences in price, availability, and access to cannabis products across Canada that have emerged post-legalization.17,18 Finally, there may be other differences in the social acceptability of cannabis use or socioeconomic, demographic, and health service access differences across provinces that may influence cannabis use patterns and more focused research in these areas continues to be needed.

Patterns of Socioeconomic Status and Cannabis Use

Substance use is influenced by various factors such as genetics, the environment, and social factors. One important social factor that influences drug use is socioeconomic status (SES), or an individual’s social and economic position in society. Certain substances may have a social gradient in usage, showing a stepped association between substance use prevalence and social position. For example, research on tobacco use in Canada has consistently shown that, on average, the smoking prevalence decreases as the socioeconomic position increases.19,20 However, the relationship between cannabis use and SES, measured by markers such as education, employment, or income, appears to be variable, and research on this topic has produced mixed findings. A further complicating factor is that socioeconomic status markers are not routinely collected in all of the surveys we used to analyze cannabis use prevalence. In addition, it is not clear whether legalization has made any substantial impact on the socioeconomic patterning of cannabis use.

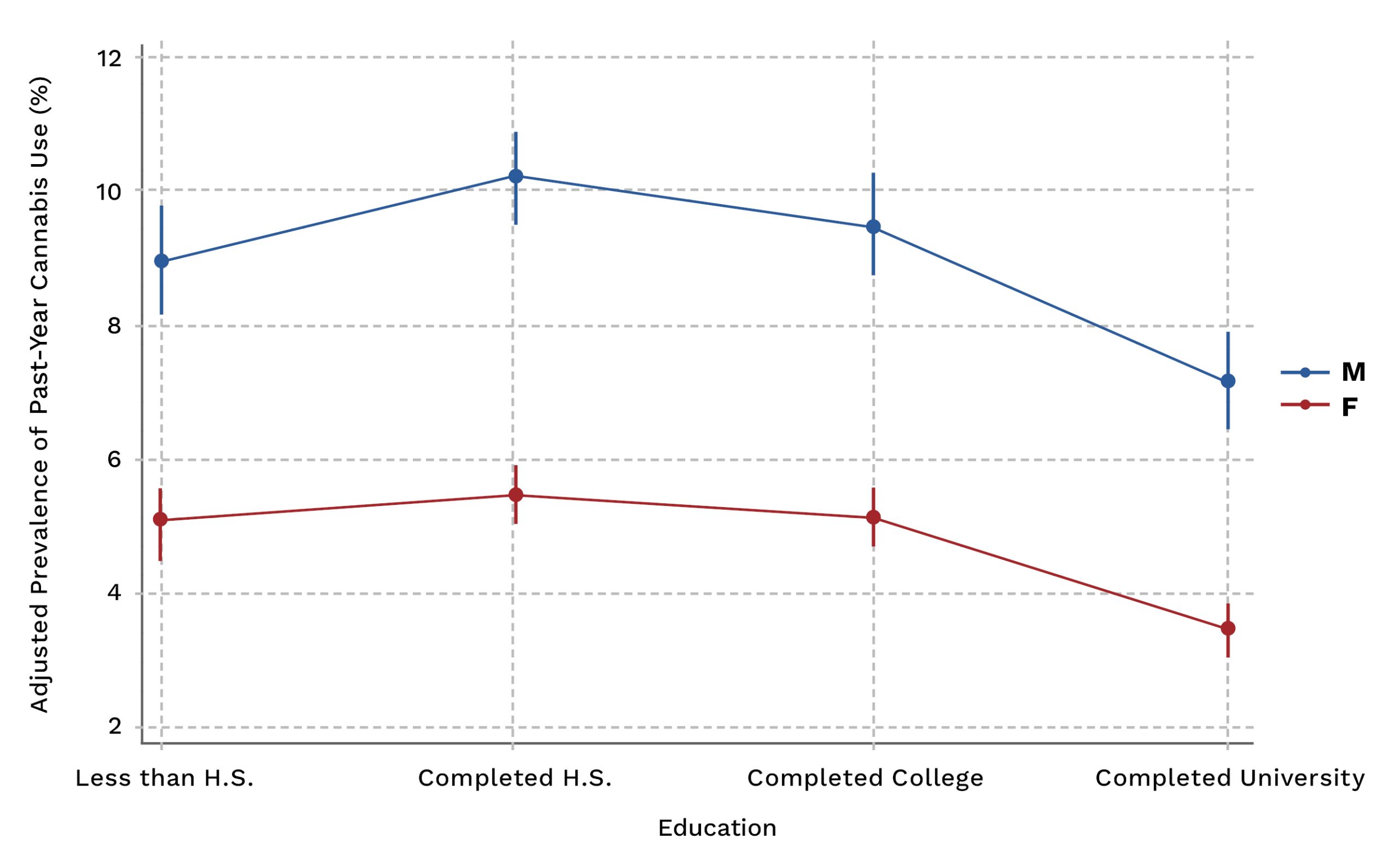

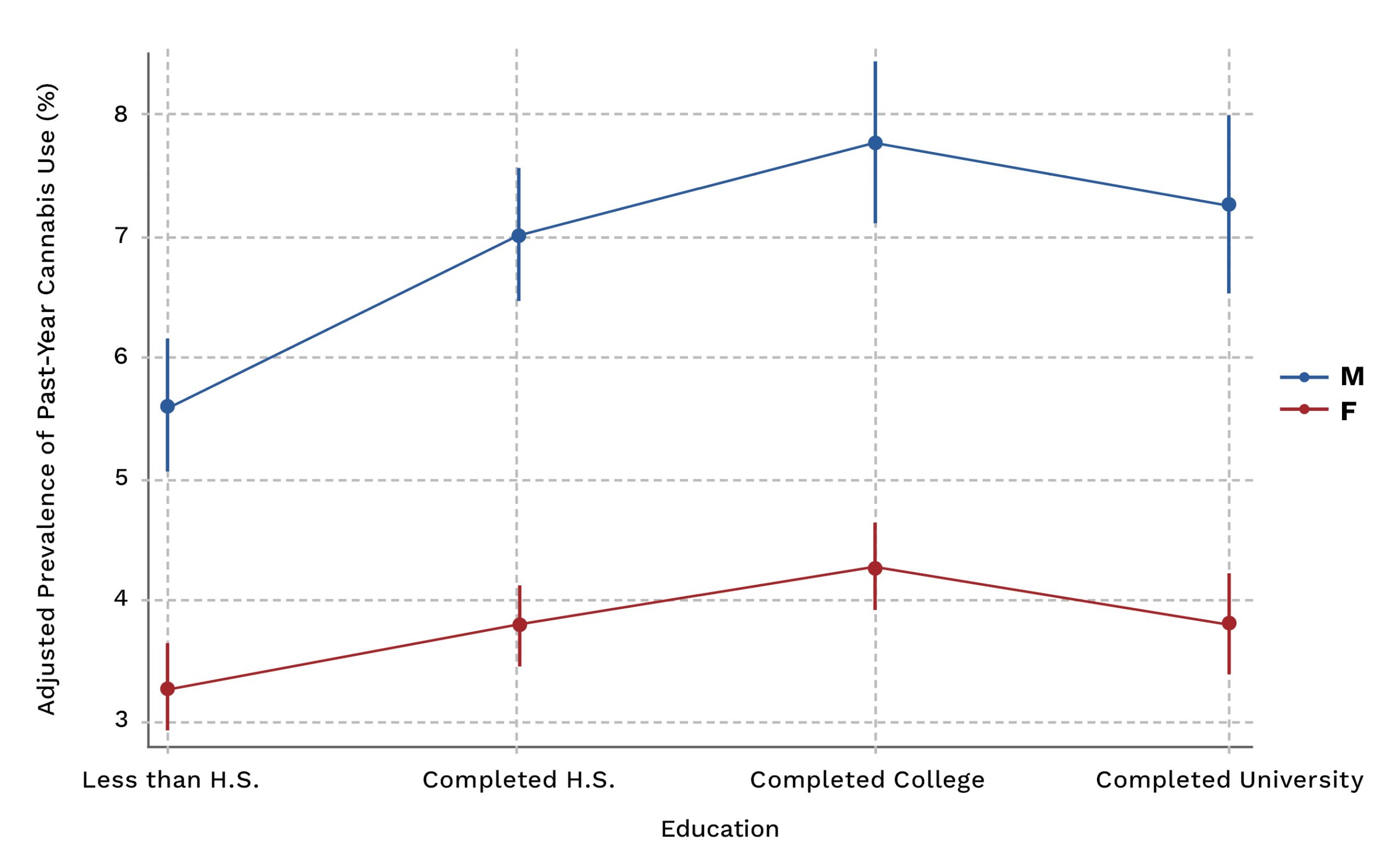

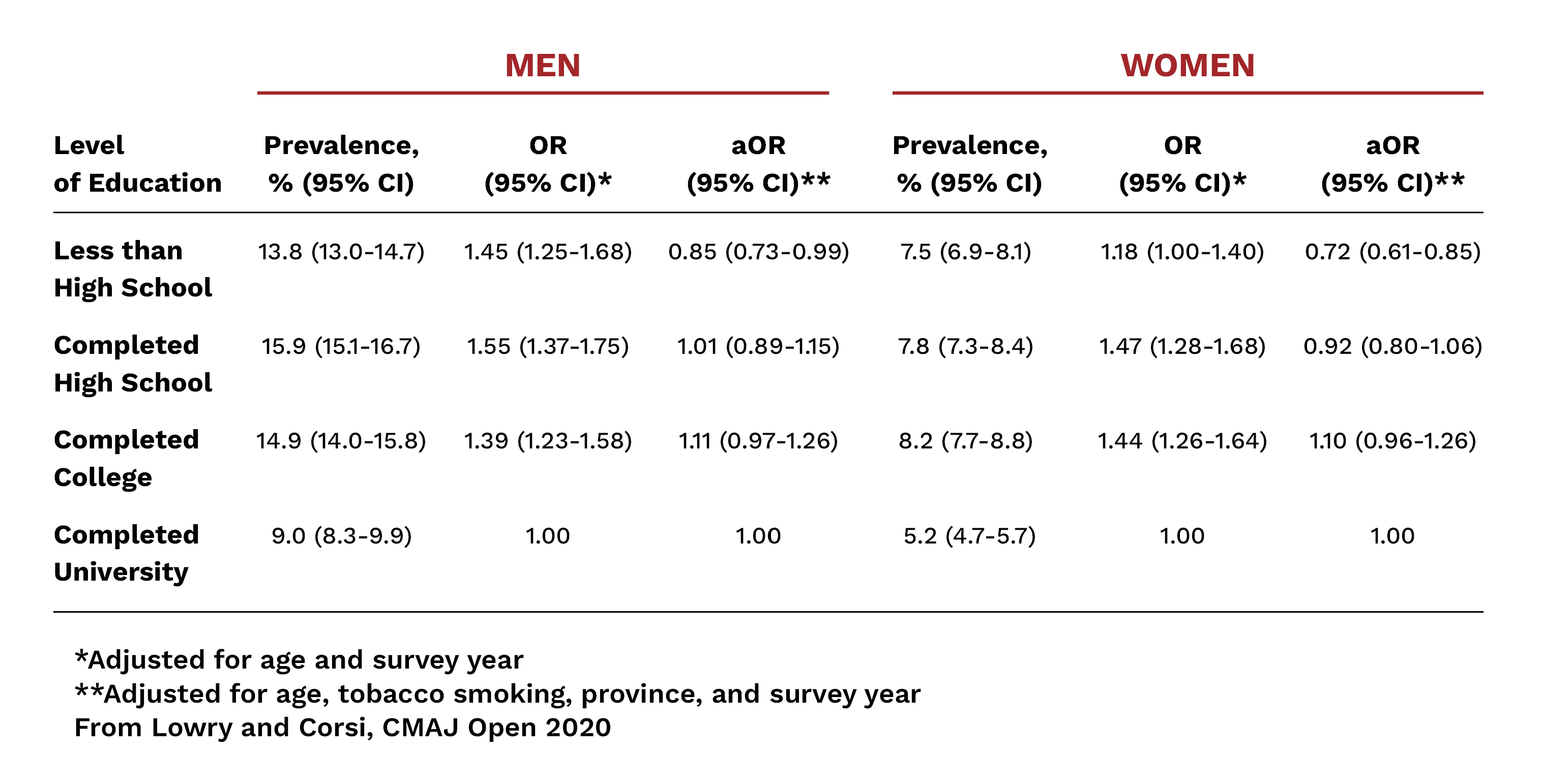

We conducted an analysis of cannabis use prevalence among different education levels as a marker for SES, covering the period between 2004 and 2017, which was the latest data we had available.15 These data revealed some interesting findings. First, cannabis use was inversely associated with the level of education after adjusting for age, and this was more apparent in men (OR:1.45; 95% CI, 1.25-1.68) when comparing less than high school vs university education (Table 1). In both men and women, however, those with either high school or college level education were also more likely to use cannabis compared to those with university degrees (Figure 4). Interestingly, accounting for tobacco smoking created a positive relationship between education and cannabis use, and males and females with completed high school, college, and university degrees were more likely to use cannabis compared to those without a high school degree (Figure 5). This finding suggests that some of the socioeconomic differentials for cannabis may be explained by tobacco use, and due to the close correlation between cannabis and tobacco smoking, we find a reversal of the SES association after controlling for tobacco.

Figure 4. Prevalence of Past-Year Cannabis Use by Education Level, by Sex, Canada 2004-2017. Estimates adjusted for age and survey year.

Figure 5. Prevalence of Past-Year Cannabis Use by Education Level, by Sex, Canada 2004-2017. Estimates were adjusted for age, survey year, and smoking status.

Table 1 Prevalence and Association Between Past-Year Cannabis Use and Level of Education Among Men and Women in Canada,

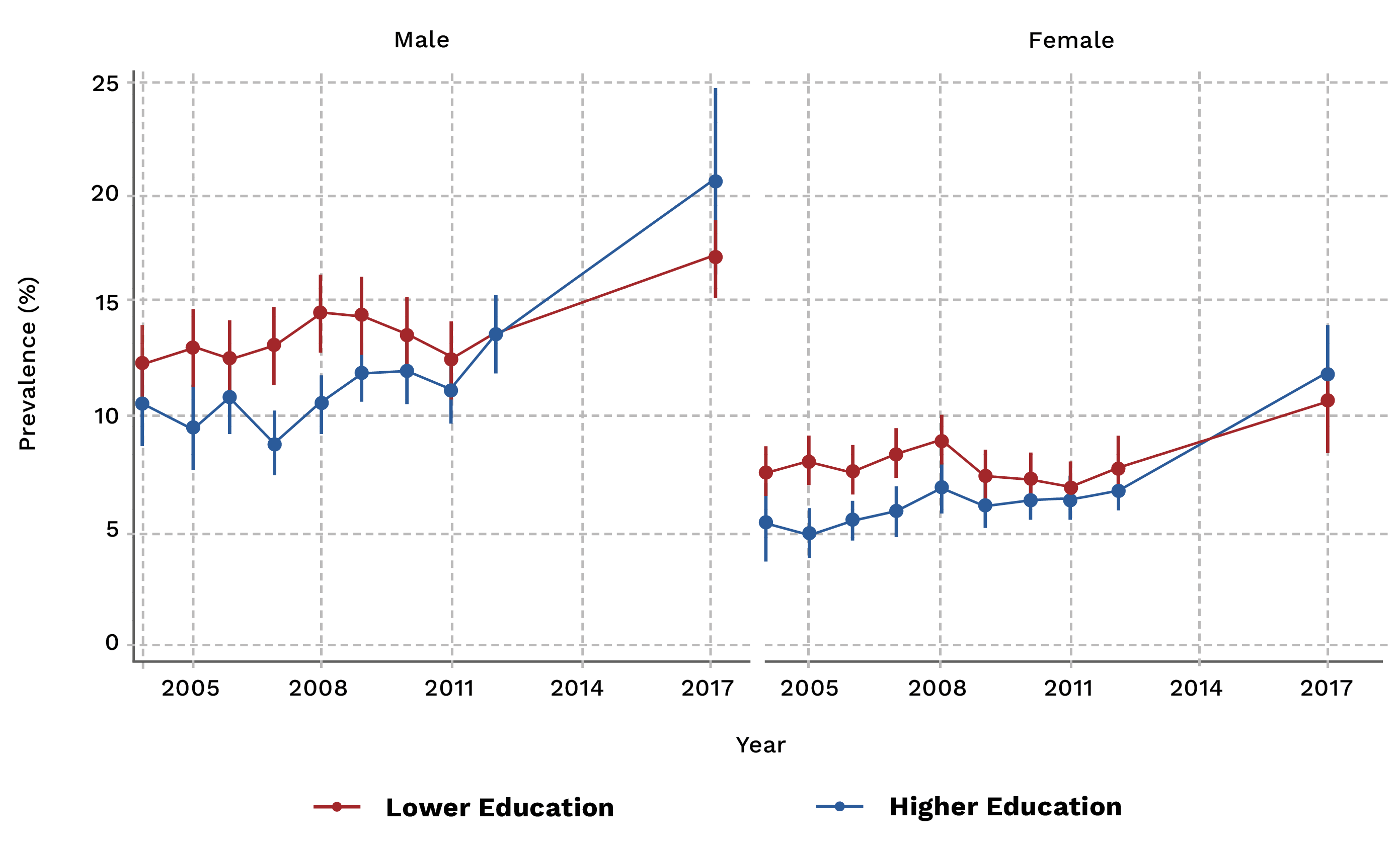

Analyses of age-adjusted trends in the prevalence of cannabis use by education level indicated heterogeneity in the rate of change by level of education between 2004 and 2017 in men and women (p-interaction<0.001) (Figure 6). Cannabis use appears to be higher among the higher educated groups in 2017, although data were not available in 2013 and 2015 and more recent data are not available. In 2017, the age-adjusted prevalence of cannabis use was 20.6% (95% CI, 16.4-24.8) among men with a university or college education, compared to 17.3% in men with a high school education. The adjusted association between education and cannabis showed a positive gradient in men in 2017 but was not statistically significant (p-trend = 0.10).

Figure 6 Age-Adjusted Trends in the Prevalence of Past-Year Cannabis Consumption by Level of Education and Sex, Canada 2004-2017

Notes: Estimates are shown with 95% confidence intervals. Data sources: Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (2004-2012), Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey (2013-2017), Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Monitoring Survey (2008-2012)

Lower education includes less than high school and completed high school; Higher education includes completed college and university.

Longitudinal studies performed in Australia and Europe have seen a decrease in the risk of cannabis consumption for those with higher educational attainment and an increased risk for youth from families with a lower socioeconomic status. 25,26 More recently, a Canadian study performed in 2023 by Benny and Colleagues reported that income inequality was significantly associated with daily cannabis use among secondary students.27

Trends in the Prevalence of Cannabis Consumption 2002-2019

We also looked generally at trends in past-year and past 30-day cannabis use in Canada between 2002 and 2019 (Figure 7) and between 2019 and 2022 (Figure 8). As we previously described, the prevalence of past-year cannabis use increased in men and women, with greater increases after 2011. In 2002, the prevalence of cannabis use was 10.2% in men and 5.7% in women. By 2019, the prevalence of cannabis use increased to 19.0% in men and 15.6% in women, adjusting for age. The odds ratio for the trend associated with the annual change in cannabis consumption between 2011 and 2019 was 1.09 (95% CI, 1.07-1.11) in men and 1.15 (1.13-1.17) in women, compared to 1.00 (95% CI, 0.99-1.01) in men and 0.98 (0.97-1.00) in women between 2002 and 2011. After adjustment for age, education, tobacco smoking, and province, the odds ratio for the 2011-2019 trend was 1.13 (95% CI, 1.09-1.17) in men and 1.15 (95% CI, 1.11-1.19) in women.

Figure 7 Age-Adjusted Trends in the Prevalence of Past-Year Cannabis Use, by Sex, Canada, 2002-2019

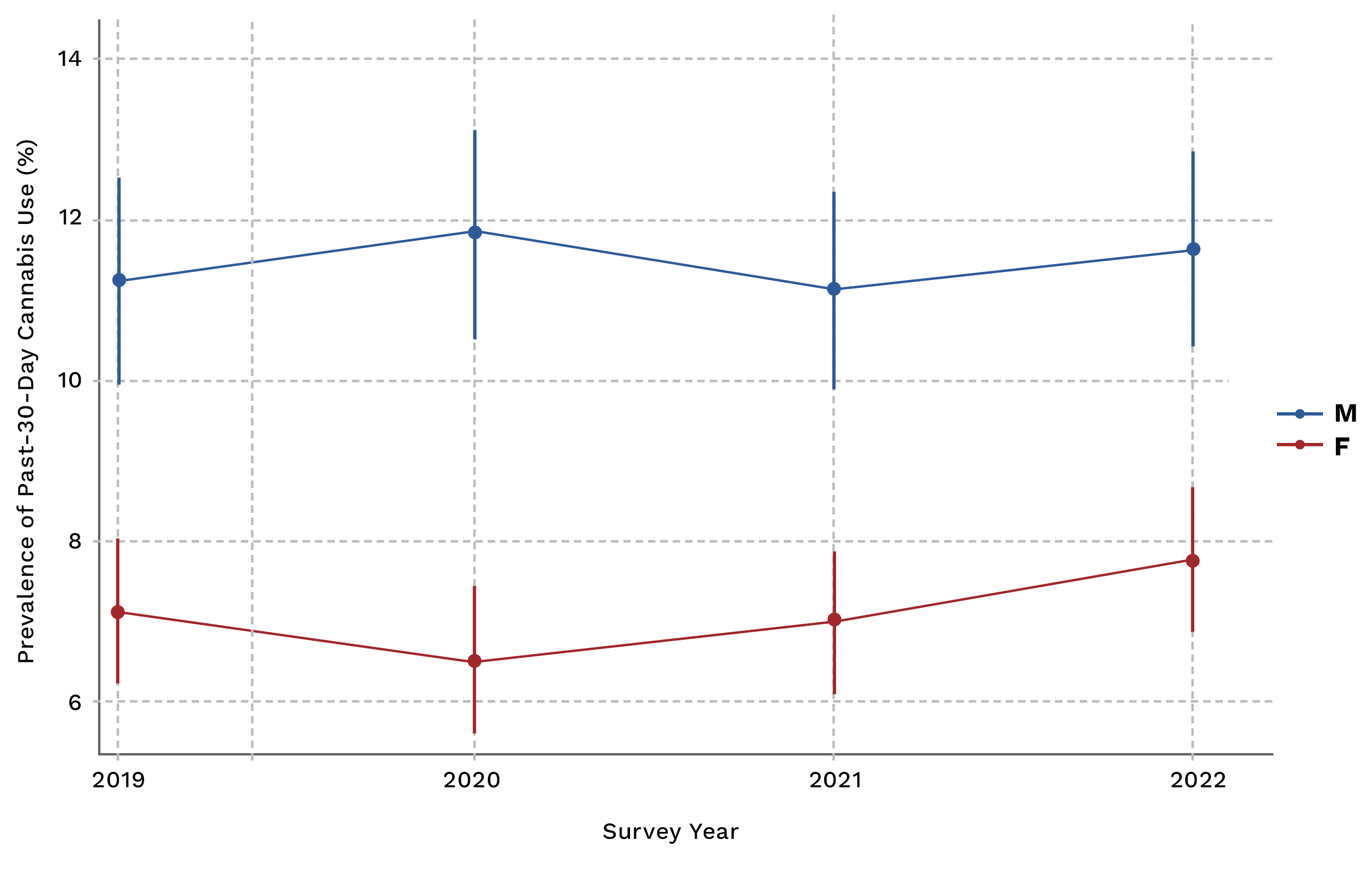

Figure 8 Age-Adjusted Trends in the Prevalence of Past-30-Day Cannabis Use, by Sex, Canada, 2019-2022

Data on past 30-day cannabis use from 2019-2022 did not reveal any significant changes over this period (Figure 8). The age-adjusted prevalence of past 30-day cannabis use in these surveys was about 11-12% in men compared to about 7% in women. There has been a moderate increase in past 30-day cannabis consumption in women, from 6.5% to 7.8% over the last 3 survey periods. However, due to the limited data points, there is still some uncertainty about whether this is a meaningful trend.

Cannabis Use in Pregnancy and Among Women of Reproductive Age

We have data from 2002-2019 on whether survey respondents were recently pregnant (n=3,243), although it was not complete for every year. Cannabis use was about 10% in this group, and 4.6% of respondents in 2019 reported using cannabis during their last pregnancy.

Cannabis use was more common among younger women aged 15-24 years who were recently pregnant. These women were 4.6 times (95% CI, 2.3-9.3) more likely to use cannabis compared to women aged 35-44 years. There was a graded and inverse association between educational attainment and cannabis use among pregnant individuals with less than a high school education associated with 3.5 times higher odds of cannabis use (95% CI, 1.36-9.14). Adjustment for tobacco smoking attenuated this association, with tobacco smoking strongly predictive of cannabis use. Current smokers had an adjusted odds ratio of 7.4 (95% CI, 3.9-14.1) for cannabis among women with a pregnancy within the past five years.

In addition, we conducted a retrospective study using data from the Better Outcomes Registry Network (BORN), a comprehensive birth registry in the province of Ontario. We aimed to analyze trends and factors associated with cannabis use during pregnancy from 2012-2017.12 To measure socioeconomic status, which is not captured in the registry, we used area-level income quantiles from the Canada Census. After adjusting for maternal age, year and population size, we found that the relative risks for cannabis use in the lowest, medium-low, middle and medium-high income quintiles compared to the highest income quintile were 3.23 (95% CI 3.02 to 3.46), 2.23 (95% CI 2.07 to 2.39), 1.65 (95% CI 1.54 to 1.78), 1.30 (95% CI 1.20 to 1.40), respectively. This indicates the presence of an inverse social gradient, with higher rates of cannabis use in the lowest income groups (about 3%) compared to the highest income (0.6%).12 Additional information on cannabis and the BORN registry can be found here, https://www.bornontario.ca/en/about-born/cannabis.aspx.

The Stigma Around Prenatal Cannabis Use

Available evidence suggests that pregnant people may use cannabis to help address unmet needs as it may be perceived as a less harmful (or more natural) way to address health concerns (including pain, nausea, anxiety, depression, and other concerns).28,29 In addition, in our qualitative interviews with patients, we noted that individuals who regularly consume cannabis before conception may be more likely to continue to consume cannabis due to routine or to maintain a sense of normalcy throughout the pregnancy. The literature also describes that people experience significant judgment around cannabis use while pregnant and parenting, suggesting that despite recent legalization, stigma may continue to limit people’s comfort in sharing their cannabis use with health and social care providers.30

Another theme in our interview research suggests that individuals who have had poor experiences when disclosing cannabis use to healthcare providers in the past may be more hesitant to disclose their consumption to healthcare personnel when pregnant. This is a cause for great concern as failing to disclose this kind of information when pregnant can not only put the child at risk but also create a stressful and isolating pregnancy for the mother.

The Stigma Around Medical Cannabis Use

Potential Health Effects of Cannabis Use

Here, we summarize some of the physical impacts that cannabis use can have on the body. Cannabinoids, which are the active chemical compounds found in cannabis, are rapidly absorbed by the bloodstream and can spread quickly throughout the body.35 Cannabinoids, including Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabidiol and cannabinol, directly impact the endocannabinoid system (ECS), a broad-spectrum modulator of the central and peripheral nervous systems.36,37 The ECS is a vast and densely packed neuromodulator system comprising cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2), endocannabinoids (endogenous cannabinoids), and the enzymes responsible for their synthesis and degradation. The cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 are present in many systems throughout the body. For example, CB1 receptors are distributed throughout the cardiovascular system. THC has been shown to cause an acute, dose-dependent increase in blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR).38–40 In a study done by Beaconsfield et al., it was found that within 10 minutes of smoking cannabis, participants had a 20-100% increase in HR, which lasted 2-3 hours.41 Cannabis inhalation has also been linked to increased levels of carboxyhemoglobin, leading to a reduced oxygen-carrying capacity in the blood.40,42 Increasing frequency of cannabis usage, specifically THC, has been linked to many adverse cardiovascular events, such as increased risk of myocardial infarction and cardiac arrhythmia.

In contrast, chronic use has been linked with cardiovascular symptoms such as hypertension and angina.38 Thrombosis Formation: CB1 and CB2 receptors have been identified on human platelets and are thought to promote thrombosis in chronic users. This could eventually lead to an increased risk of stroke or myocardial infarction in heavy users.40,43

Neurological Impairments

The CB1 receptor is present in high density throughout the central nervous system, and the interaction between cannabis consumption and these receptors and related signalling processes is thought to be responsible for several neurological and pathophysiological findings related to coordination, memory impairment, and other changes. We briefly describe some of the more acute conditions here, which may resolve after discontinuing cannabis use. Impaired coordination: Cannabis can impair motor skills and coordination, leading to impaired driving or risk of accident for up to 6 hours after ingestion, although this varies with the method of administration, concentration and biological variability.44 Short-term memory: A common side effect of cannabis use is impairment of the user’s working memory, the ability to retain and use information over short periods. The underlying mechanism for this effect remains unknown. However, it is hypothesized that this is due to an astrocyte modulation of a neuronal signalling pathway.45 Vision: Acute administration of cannabis may cause pupil constriction and conjunctival injection (red eye) or even decrease pupillary light reflex.39 These effects do not require any particular treatment but rather tend to readjust after cannabinoids have been cleared from the body.46

In addition to the acute conditions, some chronic neurological conditions and changes related to cannabis use have also been reported. For example, brain morphological changes: Studies have found that subjects who began using cannabis before the age of 17 had smaller whole brains and percent cortical gray matter47 as well as fluctuations in white matter integrity, depending on the region of the brain48–50. In addition, long-term heavy use has been associated with a decrease in hippocampal and amygdala volumes.51 Blood flow: Cannabis use during adolescence has also been associated with reduced cerebral blood flow in the Prefrontal cortex, insular and temporal regions.52 Cognition: Longitudinal studies that followed adolescents with substance use disorders found that increased cannabis use during these years of development and maturation was significantly associated with poorer attention,6 verbal memory,7 and a loss in IQ.53 Visual function: Vision, including photopic vision, depth perception and accommodative response, is thought to be affected by chronic cannabis use.54,55

Potential psychosocial harms include Anxiogenic reactions/effects: A pooled analysis of data from four double-blind, placebo-controlled studies comparing the acute pharmacodynamic effects of vaporized and oral cannabis in male and female participants revealed higher levels of THC metabolite buildup and higher levels of the drug effect restlessness and anxiousness in female participants.56 Psychosis: Cannabis is known to induce transient schizophrenia-like positive, negative and cognitive symptoms in heavy users and exacerbate symptoms in psychosis-prone and schizophrenia patients. There is increasing evidence that early and heavy use of cannabis may increase the risk of developing psychotic disorders.57–59

Other conditions potentially impacted by chronic cannabis use include metabolic and respiratory conditions, which we briefly summarize. Metabolic enzymes: THC is a strong inducer of CYP450 1A2 enzymes, which are responsible for the breakdown of caffeine and the conversion of acetaminophen into a toxic metabolite that can lead to liver injury. CBD suppresses CYP450 3A4 enzymes, responsible for the metabolism of statins, acetaminophen, benzodiazepines, and many other drugs, which can increase their half-lives and lead to drug buildup in the body. Liver disease: Animal studies, in vitro studies and human observational studies have suggested that CBD may have potential protective effects against liver disease, however these therapeutic benefits are not yet fully validated, as more robust research is needed.60–62 Respiratory Health: Long-term smoking of cannabis can lead to many respiratory issues, including damage to the airway epithelia, irritation in the lungs, shortness of breath when exercising, nocturnal wakening with shortness of breath, increased phlegm production as well as increased risk of bronchitis and lung infections.63,64 Pulmonary Immunity: Exposure to cannabis smoke is thought to impair macrophage function and decrease cytokine priming, weakening anti-bacterial immunity in the lungs of a host.64

Cannabis Use and Female Reproductive Health

We previously summarized some of the effects of cannabis use on female reproductive health and published these findings in a scientific article.13 Although cannabis use among reproductive-aged women is highly prevalent, societies rarely focus on how the use of this substance can affect the female reproductive system. As previously mentioned, the primary role of the ECS is to aid in developing the central nervous system (CNS) and the body’s response to potentially harmful stimuli and in promoting synaptic plasticity, a process by which synapses strengthen and weaken over time.65 The biological effect we observe related to consuming THC is due to its interaction with the cannabinoid receptors of the ECS. These receptors can be found in the CNS and throughout various tissues in the female reproductive tract. For example, CB1 and CB2 receptors are expressed in the female reproductive tract, including the oviduct, uterus and anterior pituitary.66 Receptors present in the female reproductive tract play a crucial role in the fertility of individuals. Studies conducted on mice using CB1 and CB2 knockout models have shown that a loss of function in these receptors can lead to abnormalities in the fertilization and implantation process.67–69

Ovarian Cycle and Hormone Levels

Exogenous cannabinoids have also been associated with other components of fertility such as hormone production, with human and animal studies both suggesting that THC can have a suppressive/inhibitory effect on hypothalamus-produced hormones such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), which are in turn responsible for stimulating prolactin, gonadotropins, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) 66. A study using data from the North Carolina Early Pregnancy cohort demonstrated that frequent and occasional cannabis users had follicular phases that lasted 2-3.5 days longer, respectively, than non-users 70. Similarly, a study using women with self-reported regular menstruation found that the luteal phase in women who co-use tobacco and marijuana is significantly shorter (~5.4 days) compared to women who solely use tobacco71. Research has also shown that smoking a single 1-g joint can reduce plasma levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) by up to 30% 72. Suppressing LH levels can have grave consequences on fertility, such as a reduction in fecundity through delayed or absent ovulation, as well as the termination of an early pregnancy. This is because a surge of LH is necessary to signal to your ovary to release a mature egg for fertilization and aid in progesterone production by the corpus luteum, which is needed to support the early stages of pregnancy. As a consequence, we are seeing that cannabis users are more likely to have anovulatory cycles compared to non-users 70.

Time to Conception and Fertility

No significant association has been found between cannabis use and time to conception.73 However, researchers have found that the risk of infertility is greater for women who have used cannabis within 1 year of trying to become pregnant naturally or through in-vitro fertilization (IVF) and gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT) when compared to women who have never consumed cannabis.74,75

Cannabis Use and Associations with Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes

In pregnancy, cannabinoids can enter the fetal bloodstream via the placenta.36,76 Cannabinoids can perturb the fetal ECS, which is present and active from early embryonic stages and modulates neurodevelopment into adulthood.36 Another important aspect of cannabis use in pregnancy is that the lipophilic nature of THC, combined with its long half-life in fatty tissues, results in extended exposure to fetal tissues, even after the mother stops using the drug.77,78 Epidemiological studies have suggested associations between cannabis use in pregnancy and maternal outcomes including, anemia,79,80 gestational diabetes,81 Cesarian delivery,81 and placental abruption.9,80 Epidemiological data also suggests associations between cannabis use in pregnancy and perinatal outcomes, including stillbirth,82,83 preterm birth9,80,82,84,85, low birth weight,79,85–87 small for gestational age (SGA),9,80,82,84,85 growth restrictions,80,86,88,89 increased admission/transfer to the NICU,9,79,80,85 5-minute Apgar score less than 7,9,80 increase in tremors, startle response and deficient habituation to visual stimuli.90 These outcomes are often associated with longer hospital stays and more complex health and social needs throughout early childhood.9,85

Cannabis Use and Breastfeeding

The risk associated with maternal cannabis use is present even after the delivery of the fetus as nursing children continue to be exposed to cannabinoids through maternal breastmilk anywhere from 2-6 weeks after consumption.91,92 The low molecular weight and lipid solubility of cannabinoids contribute to their propensity for transfer into breast milk.35,92–94 Thus, the fat composition of the mother’s breastmilk can further influence the cannabinoid concentration in the breastmilk passed on to the child, which their body will attempt to metabolize.95,96

Cannabinoid concentrations in breast milk can reach up to 8 times higher than those found in maternal serum, depending on the extent of maternal consumption.97 This heightened or repeated exposure during early development may have consequences on the infant, including short and long-term effects. One possible side effect is drowsiness, which can affect a baby’s ability to latch and suck properly, leading to poor weight gain.98

Furthermore, it can disrupt the ECS and negatively impact child development at multiple stages of their life. For example, Astley & Little explored the relationship between infant exposure to cannabis through maternal milk and infant motor and mental development at one year of age, in 68 infants with mothers who breastfed and consumed cannabis and matched controls. Here, they found a significant association between cannabis exposure through breastmilk during the fetus’ first month and a decrease (14-point) in the Bayley index of infant motor development after adjusting for maternal smoking, drinking, and cocaine use during pregnancy and lactationi.99

i More on the neurodevelopment impacts of cannabis can be found below.

Further robust research and public education are sorely needed on the health outcomes of infants exposed to cannabis through breastmilk, as just over 50% of mothers in Canada choose to breastfeed for at least 4 months after the birth of their child. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canada’s Breastfeeding Progress Report 2022. Government of Canada 2022.

Cannabis Use and Child Neurodevelopment

Fetal and infant exposure to cannabis during pregnancy and breastfeeding can disrupt the fetal ECS, which modulates neurodevelopment from early embryonic stages into adulthood. It appears that the duration and magnitude of exposure appear to be critical components in understanding the potential neurodevelopmental impacts of maternal cannabis use on offspring.100 Studies have indicated that prenatal exposure to cannabis through maternal use can cause decreases in concentration and attention among offspring compared to children of mothers who abstain.101

Using data from the Ottawa Prospective Study, that followed mothers and their children born from 1980-1983, Fried and Makin investigated the risks of marijuana consumption during pregnancy on the development of the neonate’s behaviour. From this, they found that the neonates that were exposed to maternal cannabis consumption (on average 1 joint/week) had increased startle response, tremors and deficient habituation to visual stimuli compared to unexposed neonates.90

In addition, at 4 years of age, the exposed infants had lower scores on verbal and memory domains of McCarthy Scales of Children Ability.102 Similar to this, Day and colleagues’ study, published in 1994, showed evidence of a negative association between first or second-trimester marijuana use and short-term memory and verbal reasoning in children of 3 years of age.103 However, no effect was found at later ages after adjusting for home environments.90,104,105 Paul et al.’s 2021 study performed in the United States, found that prenatal exposure after maternal knowledge of pregnancy was in fact associated with an increase in risk for psychopathology (defined as psychotic-like experiences and internalizing, externalizing, attention, thought and social problems), during childhood, whereas the risks from exposure only before maternal knowledge of pregnancy did not differ from that of no exposure for any symptoms of psychopathology after adjusting for covariates.106 Finally, in our own analyses of birth registry data in Ontario, Canada, we followed children born between 2007-2012 for up to seven years to evaluate the association between cannabis exposure in pregnancy and neurodevelopment outcomes in childhood. We found that the risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis was 50% higher for children exposed to cannabis in utero compared to those unexposed.8

On the Plausibility of Perinatal Cannabis Exposure and Outcomes

To summarize these data, many epidemiological studies show robust associations between maternal cannabis use in pregnancy and several perinatal outcomes and aspects of cognitive development. Despite the biologic plausibility of fetal ECS exposure to cannabinoids via placental transfer,77,107 establishing a causal relationship between prenatal cannabis use and adverse perinatal outcomes using standard epidemiological approaches remains challenging.108 Most of the studies above have significant limitations, including the reliance on self-reported cannabis use, which may underestimate exposure,109 due to feelings of guilt, fear of legal action or stigma.110,111 There is also a large potential for confounding related to concomitant use of tobacco, alcohol, and other substances in pregnancy,112,113 and the strong association between maternal cannabis use and socioeconomic status.114 It is essential to consider these and other potential limitations when interpreting associations between maternal cannabis exposure and pregnancy outcomes, and we are working on an approach to strengthen the observational evidence using different study designs and approaches to mitigate potential biases. For example, we are working on improving the measurement of prenatal cannabis use and concomitant tobacco using biospecimen analysis115,116 to quantify prenatal cannabis and tobacco use objectively. We are also comparing different study designs, for example, individual-level versus ecological- or population-level analyses.

Cannabis Use and Youth Mental Health

The human brain continues to develop and mature until an individual reaches 25 years of age, making the period from embryonic stages to adulthood critical for brain development.117 The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is typically the last part of the brain to develop in an individual. This part of the brain is essential in the regulation of our thoughts, actions and emotions and its dysfunction is a central feature of many psychiatric disorders such as ADHD, PTSD, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.118 Although not fully understood to this day, many scientists believe that adverse mental health or mental illness is tied to problems with neurotransmission in the brain, such as lower levels of production or uptake of neurotransmitters119 , that can be caused by environmental, genetic and/or social factors, during development and throughout adulthood. In addition, regular cannabis use in youth can also structurally damage the brain by lowering the brain’s volume, creating different folding patterns, thinning the cortex and reducing neural connectivity and white matter integrity.120

It is said that the ECS, found throughout the nervous system of individuals, is linked to feelings of fear and anxiety as it is considered a regulatory buffer system for emotional responses and is heavily impacted by environmental factors such as cannabis consumption. Some of the most robust evidence on cannabis use and health suggests that cannabis use in youth, a time of development, is associated with many adverse mental health outcomes, including increased rates of depression 121–123, suicidal behaviors121, anxiety 122 and self-reported poor mental health.124 In fact, an Australian cross-sectional study found that cannabis consumption was a common habit among young people who presented themselves for mental health services 125. Using cross-sectional data collected in the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study (OCHS), Girgis et al. investigated the associations between cannabis use and internalizing or externalizing symptoms in adolescents aged 12-17. After stratifying by sex at birth and controlling for age, smoking, binge drinking, positive parenting and negative/ineffective parenting, a significant association was observed between cannabis use and elevated externalizing and internalizing symptoms in youth. However, the effects were significantly higher in females than males.126 In a study performed by Sultan and colleagues, they investigated the association between cannabis use and adverse psychosocial events in youth aged 12-17 across the United States. Interestingly, they found that non-disordered cannabis users (cannabis users who do not meet the threshold for diagnostic criteria of cannabis use disorder) had a greater association with major depressive episodes and suicidal intentions compared to non-users and individuals with cannabis use disorder127 – revealing that there is a substantial risk to youth mental health regardless of the magnitude of cannabis consumed. Despite these findings, Canadian youth (15-24 yrs) have some of the highest rates of cannabis consumption worldwide128 with 37% of youth aged 16-19 years old and 50% of youth aged 20-24 years old reporting past year use of cannabis, compared to only 25% of people aged 25 years and older.129

Conclusion

This report explores the complex landscape of cannabis-related policies, demographic trends, and socioeconomic factors in Canada over five years since legalization. In 2018, the Cannabis Act created a legal framework to protect youth, promote public health, and eliminate illegal profits. Our analysis of provincial and territorial regulations reveals some important variations, including differences in legal age for purchase and possession and restrictions on cannabis cultivation and consumption areas. Moreover, our examination of cannabis usage trends highlights nuanced patterns, with significant disparities based on gender, age, and region. Tobacco smoking also emerges as a significant factor, underscoring the interconnectedness of substance use behaviours.

We explored the relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and cannabis use, with cannabis use notably influenced by education levels and tobacco use. SES markers exhibit varying impacts across demographics, calling for a nuanced understanding of the socioeconomic patterning of cannabis consumption in addition, more robust data on SES and cannabis use from biomarkers may be required to elucidate this relationship fully. The geographic variation in cannabis use further underscores the need for targeted research to unveil the complex interplay of policy differences, social acceptance, and regional dynamics.

As cannabis legislation and regulations evolve, our report sheds light on the imperative for ongoing research and adaptability in policymaking. The examination of trends over the years provides insights into shifting prevalence rates and potential social gradients, prompting the need for continuous monitoring and assessment. Additionally, our exploration of cannabis use during pregnancy underscores the persistence of stigma and the importance of fostering open dialogues between healthcare providers and individuals, emphasizing the necessity for supportive and non-judgmental healthcare environments.

We also explored two key topics related to cannabis: the stigma surrounding medical cannabis use and the potential health effects of cannabis use. Regarding the stigma, individuals with chronic or terminal illnesses face significant barriers due to societal perceptions and judgment. Medical professionals, family members, and society at large often label medicinal cannabis users negatively, hindering open discussions and recommendations from healthcare providers. The report suggests combating this stigma through community-based initiatives like public education campaigns and informative platforms.

There are numerous potential physiological impacts of cannabis use. We emphasize that cannabis is not a benign substance, and there are many unknowns around the roles of various cannabinoids, such as THC, CBD, and cannabinol, in affecting the endocannabinoid system (ECS), which modulates the nervous system. Cannabis use has been linked to acute cardiovascular effects, potential thrombosis formation, and various neurological impairments, including impaired coordination, short-term memory issues, and vision changes. In addition, there have been many psychosocial harms identified, such as anxiogenic reactions and the potential induction of psychosis in heavy users.

Our prior research has been largely focused on cannabis use and female reproductive health. Here, we summarize some of the effects of cannabis on the ECS in the female reproductive tract and its influence on the ovarian cycle and hormone levels. We present associations with pregnancy and birth outcomes, including stillbirth, preterm birth, low birth weight, and increased health complications for infants. We also examine breastfeeding, highlighting the risk of cannabinoid exposure to nursing children and its potential effects on development.

There is a growing body of literature on the impact of cannabis on child neurodevelopment, for example, associations with decreased concentration, attention, and negative behavioural outcomes. In addition, there is ongoing brain development until the age of 25 and cannabis use, especially during youth, can structurally damage the brain. Other concerning associations between cannabis use in youth and adverse mental health outcomes reported in the literature include depression, suicidal behaviours, and anxiety. Canadian youth exhibit high rates of cannabis consumption, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions and awareness campaigns.

While it is known that exposure to cannabinoids during fetal development can happen through placental transfer, establishing a causal link between maternal cannabis use during pregnancy and negative perinatal outcomes remains difficult. The available research is limited by factors such as self-reported cannabis use, which may not accurately reflect exposure due to societal pressures. Additionally, confounding factors like tobacco and alcohol use, socioeconomic status, and other substances used during pregnancy, make interpretation challenging. Despite these challenges, we are actively involved in ongoing efforts to improve the observational evidence. We are working to improve measurement methods, such as biospecimen analysis, to quantify prenatal cannabis and tobacco use objectively.

References

Government of Canada. A framework for the legalization and regulation of cannabis in canada. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2016.

Health Canada. Canadian Cannabis Survey 2023: Summary. 2023.

Carliner H, Brown QL, Sarvet AL, Hasin DS. Cannabis use, attitudes, and legal status in the U.S.: A review. Prev Med. 2017;104:13-23.

Pacula RL, Powell D, Heaton P, Sevigny EL. Assessing the effects of medical marijuana laws on marijuana use: the devil is in the details. J Policy Anal Manage. 2015;34(1):7-31.

McGinty EE, Niederdeppe J, Heley K, Barry CL. Public perceptions of arguments supporting and opposing recreational marijuana legalization. Prev Med. 2017;99:80-6.

Tapert SF, Granholm E, Leedy NG, Brown SA. Substance use and withdrawal: neuropsychological functioning over 8 years in youth. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8(7):873-83.

Tait RJ, Mackinnon A, Christensen H. Cannabis use and cognitive function: 8-year trajectory in a young adult cohort. Addiction. 2011;106(12):2195-203.

Corsi DJ, Donelle J, Sucha E, Hawken S, Hsu H, El-Chaâr D, Bisnaire L, Fell D, Wen SW, Walker M. Maternal cannabis use in pregnancy and child neurodevelopmental outcomes. Nature Medicine. 2020;26(10):1536-40.

Corsi DJ, Walsh L, Weiss D, Hsu H, El-Chaar D, Hawken S, Fell DB, Walker M. Association Between Self-reported Prenatal Cannabis Use and Maternal, Perinatal, and Neonatal Outcomes. JAMA. 2019;322(2):145-52.

Corsi D. Epidemiological challenges to measuring prenatal cannabis use and its potential harms. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2020;127(1):17.

Corsi DJ. The potential association between prenatal cannabis use and congenital anomalies. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2020;14(6):451-3.

Corsi DJ, Hsu H, Weiss D, Fell DB, Walker M. Trends and correlates of cannabis use in pregnancy: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada from 2012 to 2017. Can J Public Health. 2019;110(1):76-84.

Corsi DJ, Murphy MS, Cook J. The effects of cannabis on female reproductive health across the life course. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2021;6(4):275-87.

Cresswell L, Espin-Noboa L, Murphy MS, Ramlawi S, Walker MC, Karsai M, Corsi DJ. The volume and tone of Twitter posts about cannabis use during pregnancy: protocol for a scoping review. JMIR Research Protocols. 2022;11(3):e34421.

Lowry DE, Corsi DJ. Trends and correlates of cannabis use in Canada: a repeated cross-sectional analysis of national surveys from 2004 to 2017. Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal. 2020;8(3):E487-E95.

Sharif A, Bombay K, Murphy MS, Murray RK, Sikora L, Cobey KD, Corsi DJ. Canadian Resources on Cannabis Use and Fertility, Pregnancy, and Lactation: Scoping Review. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting. 2022;5(4):e37448.

Myran DT, Staykov E, Cantor N, Taljaard M, Quach BI, Hawken S, Tanuseputro P. How has access to legal cannabis changed over time? An analysis of the cannabis retail market in Canada 2 years following the legalisation of recreational cannabis. Drug and alcohol review. 2022;41(2):377-85.

Mahamad S, Wadsworth E, Rynard V, Goodman S, Hammond D. Availability, retail price and potency of legal and illegal cannabis in Canada after recreational cannabis legalisation. Drug and alcohol review. 2020;39(4):337-46.

Corsi DJ, Subramanian S, Lear SA, Chow CK, Teo KK, Boyle MH. Co-variation in dimensions of smoking behaviour: a multivariate analysis of individuals and communities in Canada. Health & Place. 2013;22:29-37.

Corsi DJ, Lear SA, Chow CK, Subramanian S, Boyle MH, Teo KK. Socioeconomic and geographic patterning of smoking behaviour in Canada: a cross-sectional multilevel analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57646.

Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Sarvet AL. Time trends in US cannabis use and cannabis use disorders overall and by sociodemographic subgroups: a narrative review and new findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45(6):623-43.

Patrick ME, Wightman P, Schoeni RF, Schulenberg JE. Socioeconomic status and substance use among young adults: a comparison across constructs and drugs. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(5):772-82.

Azofeifa A, Mattson ME, Schauer G, McAfee T, Grant A, R L. National Estimates of Marijuana Use and Related Indicators — National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2002–2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016.

Zofeifa A, Mattson ME, Schauer G, McAfee T, Grant A, Lyerla R. National Estimates of Marijuana Use and Related Indicators — National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2002–2014. 2016. Contract No.: SS-11.

Chan GCK, Leung J, Quinn C, Weier M, Hall W. Socio-economic differentials in cannabis use trends in Australia. Addiction. 2018;113(3):454-61.

Gerra G, Benedetti E, Resce G, Potente R, Cutilli A, Molinaro S. Socioeconomic Status, Parental Education, School Connectedness and Individual Socio-Cultural Resources in Vulnerability for Drug Use among Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4).

Benny C, Steele BJ, Patte KA, Leatherdale ST, Pabayo R. Income inequality and daily use of cannabis, cigarettes, and e-cigarettes among Canadian secondary school students: Results from COMPASS 2018-19. Int J Drug Policy. 2023;115:104014.

Bartlett K, Kaarid K, Gervais N, Vu N, Sharma S, Patel T, Shea AK. Pregnant Canadians’ Perceptions About the Transmission of Cannabis in Pregnancy and While Breastfeeding and the Impact of Information From Health Care Providers on Discontinuation of Use. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020;42(11):1346-50.

Skelton KR, Donahue E, Benjamin-Neelon SE. Measuring cannabis-related knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, motivations, and influences among women of reproductive age: a scoping review. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):95.

Hines L. The treatment views and recommendations of substance abusing women: A meta-synthesis. Qualitative Social Work. 2013;12(4):473-89.

Melnikov S, Aboav A, Shalom E, Phriedman S, Khalaila K. The effect of attitudes, subjective norms and stigma on health-care providers’ intention to recommend medicinal cannabis to patients. Int J Nurs Pract. 2021;27(1):e12836.

Bottorff JL, Bissell LJL, Balneaves LG, Oliffe JL, Capler NR, Buxton J. Perceptions of cannabis as a stigmatized medicine: a qualitative descriptive study. Harm Reduction Journal. 2013;10(1):2.

Troup LJ, Erridge S, Ciesluk B, Sodergren MH. Perceived Stigma of Patients Undergoing Treatment with Cannabis-Based Medicinal Products. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(12).

Nayak MM, Revette A, Chai PR, Lansang K, Sannes T, Tung S, Braun IM. Medical cannabis-related stigma: cancer survivors’ perspectives. J Cancer Surviv. 2023;17(4):951-6.

Battista N, Sergi M, Montesano C, Napoletano S, Compagnone D, Maccarrone M. Analytical approaches for the determination of phytocannabinoids and endocannabinoids in human matrices. Drug Test Anal. 2014;6(1-2):7-16.

Richardson KA, Hester AK, McLemore GL. Prenatal cannabis exposure – The “first hit” to the endocannabinoid system. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2016;58:5-14.

Walker OS, Holloway AC, Raha S. The role of the endocannabinoid system in female reproductive tissues. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12(1):3.

Subramaniam VN, Menezes AR, DeSchutter A, Lavie CJ. The Cardiovascular Effects of Marijuana: Are the Potential Adverse Effects Worth the High? Mo Med. 2019;116(2):146-53.

Fant RV, Heishman SJ, Bunker EB, Pickworth WB. Acute and residual effects of marijuana in humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60(4):777-84.

Latif Z, Garg N. The Impact of Marijuana on the Cardiovascular System: A Review of the Most Common Cardiovascular Events Associated with Marijuana Use. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020;9(6):1925.

Beaconsfield P, Ginsburg J, Rainsbury R. Marihuana smoking. Cardiovascular effects in man and possible mechanisms. N Engl J Med. 1972;287(5):209-12.

Sánchez Artiles AE, Awan A, Karl M, Santini A. Cardiovascular effects of cannabis (marijuana): A timely update. Phytotherapy Research. 2019;33(5):1592-4.

Greger J, Bates V, Mechtler L, Gengo F. A Review of Cannabis and Interactions With Anticoagulant and Antiplatelet Agents. J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;60(4):432-8.